1940

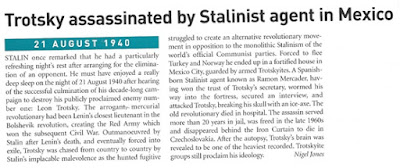

Real name Lev ben David Bronstein. Born Yanovka, Ukraine, October 26th 1879. Educated in Odessa. First arrest & transportation to Siberia, 1898 (escaped to London, 1902; spotted in Vienna, 1913 - click here). President of the St Petersburg Soviet, 1905. Commissar for Foreign Affairs, 1917. Commissar for War, 1918. Ousted from the Politburo, expelled from the Party, and exiled internally, 1927, externally 1929. Sentenced to death by Soviet Law, 1937. Assassinated in Mexico, August 20th 1940.

Real name Lev ben David Bronstein. Born Yanovka, Ukraine, October 26th 1879. Educated in Odessa. First arrest & transportation to Siberia, 1898 (escaped to London, 1902; spotted in Vienna, 1913 - click here). President of the St Petersburg Soviet, 1905. Commissar for Foreign Affairs, 1917. Commissar for War, 1918. Ousted from the Politburo, expelled from the Party, and exiled internally, 1927, externally 1929. Sentenced to death by Soviet Law, 1937. Assassinated in Mexico, August 20th 1940.

Trotsky, the intellectual heart of the Revolution, whose goal was not that of Lenin nor of Stalin - the replacement of the Despotism of the Czars by the Dictatorship of the Proletariat - but the liberation of all human beings from the history of vassaldom, of forced innumeracy and illiteracy, of inhabiting a world in which the tiny majority who form the ruling class take unto themselves all power and all wealth, and care nothing, less than nothing in some cases, about the values or ethics or morals or principles that would be necessary if Truth, Justice, Compassion, and ultimately Idealism itself, are to bear fruit for all of Humankind. Trotsky, who would have overthrown all dictatorships, including that of the Proletariat... but Trotsky does not need me to defend, justify or vindicate him. Among his many writings, the speech he delivered in Copenhagen, in November 1932, after Stalin had finally defeated him by deporting him, says what he felt it necessary to say. Click here to read it.

|

| http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-33909385 |

Unusual for the BBC to get these things wrong... the assassination was on the 20th, but he lingered on into the early hours of the 21st. The killer was named Jacques Mornard, an alias, like Trotsky. His real name was sometimes Ramón del Rio, sometimes Ramón Mercader, on his birth and death certificates Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río.

Click here for Trotsky's grandson's personal account of the assassination.

Trotsky is a shoe-in for my inventory of the overlooked and unfairly derogated great men of history, but the man I really want to write about here isn't Trotsky; rather it's one of his closest companions in the Revolution, like him a refugee in Mexico, like him an intellectual of enormous stature who simply terrified the morons who ran the Bolshevik party and who therefore had no choice, as the stupid always do when no other weapon is available to them, but to use fists and guns and sometimes torture to prove who is in charge, usually of making the world a far worse place. Violence, as we all know, is the last refuge of the ignorant.

Trotsky is a shoe-in for my inventory of the overlooked and unfairly derogated great men of history, but the man I really want to write about here isn't Trotsky; rather it's one of his closest companions in the Revolution, like him a refugee in Mexico, like him an intellectual of enormous stature who simply terrified the morons who ran the Bolshevik party and who therefore had no choice, as the stupid always do when no other weapon is available to them, but to use fists and guns and sometimes torture to prove who is in charge, usually of making the world a far worse place. Violence, as we all know, is the last refuge of the ignorant.

The man in question is Victor Serge - generally mispronounced à la Français with a soft "g" and a silent "e", though at least it hints at the correct Russian, which is Sergei; Victor Lvovich Kibalchich (В.Л. Кибальчич) before he took the nom de guerre - a man whose life was so deeply involved in the major events of his day, and so colourful, and with such close personal knowledge of every one of the principal protagonists, that one has to hope he wrote it all down in an auto-biography; and thankfully he did, borrowing the title from the anarchist Pëtr Kropotkin's 1899 "Memoirs of A Revolutionist", but changing "revolutionist" to "revolutionary".

You can support the cause of world Capitalism by purchasing a copy at Amazon.com, or you can read it for free by clicking here, or here (same edition, either way). You can also take a short-cut to his life-tale here; given just how thorough that site is, I am not going to waste time telling more than the broken bones of it here. More interesting, to me anyway, because I have read his Memoir, are some of the passages I found it irresistible to highlight…

Born in Belgium in 1890, to Russian parents whose revolutionary antics had forced them to flee into exile, he was amongst those Belgians who protested the brutal colonial regime in the Congo (see my monograph on Gide on November 22), but almost alone in protesting colonialism per se, a century ahead of Edward Said or Kamel Daoud, the man who re-wrote Camus' "L’Etranger". Virtually uneducated, at least in the formal sense of attending schools, he worked as a typestetter in a French mining village, then lived among the beggars in Paris while editing an anarchist magazine and spending most of the Great War in a high security prison for refusing to testify against other anarchists. Released in 1917, it would take him two years to find a way to join the revolution in his homeland, now under his pseudonym, Victor Serge.

He spent the next seventeen years in Russia, as a member of a militia in the civil war, as the senior investigator of the archives of the Tsar's secret police, as a Comintern official with a passport to travel and spread revolution, but mostly fighting against the failures of the revolution from the inside - he supported democracy and an elected legislature, human rights and egalitarian social policies, was first appalled, then disgusted, by the despotic aspirations of the Bolsheviks, and became the man who people turned to when they heard whispers of their imminent arrest, or that of people close to them. He fought for a free press and against the secret police, fought for civil liberties and against closed trials, and when it came to the death penalty, an instance of which he witnessed in Paris, he was unequivocal:-

“When in the morning I returned to that spot on the boulevard, a huge policeman, standing on the square of fresh sand that had been thrown over the blood, was attentively treading a rose into it. A little farther off, leaning against a wall, Ferral was gently wringing his hands: ‘Society is so iniquitous!’... From this day dates the revulsion and contempt that is aroused in me by the death penalty, which replies to the crime of the primitive, the retarded, the depraved, the half-mad, or the hopeless, by nothing short of a collective crime, carried out coldly by men invested with authority, who believe that they are therefore innocent of the pathetic blood they shed. As for the endless torture of life imprisonment or of very lengthy sentences, I know of nothing more stupidly inhuman.” (page 36)

Hardly surprising then that, despite knowing everyone who mattered and being regarded by them as one of the intellectual prodigies of the revolution, he was expelled from the Communist Party in the late 1920s, and then jailed on Stalin's personal orders. In jail, he used the time to write, always in French though he spoke five languages with equal fluency, the beginning of "Memoirs of a Revolutionary", which are probably his most important book, but also novels such as "Conquered City" and "The Case of Comrade Tulayev", and a good deal of poetry, much of it now available in James Brook's translation under the title "A Blaze In A Desert".

If we roused the peoples and made the continents quake

If we began to make everything anew with these dirty old stones,

these tired hands, and the meagre souls that were left us,

it was not in order to haggle with you now,

sad revolution, our mother, our child, our flesh,

our decapitated dawn, our night with its stars askew...

No sooner was he released than Stalin signed papers exiling him to Orenburg in the high Urals. But within three years his admirers in the west had persuaded Stalin to deport rather than exile him, and in 1936 he was back in France, able to witness from a safe distance the Great Purge in which most of his comrades were evaporated, in which his wife Liuba Russakova was hounded into a psychiatric hospital, and his mother-in-law with her sons and their wives disappeared into the Gulag; the writings he had left behind suffered the fate that would have been his own had he remained.

No sooner was he released than Stalin signed papers exiling him to Orenburg in the high Urals. But within three years his admirers in the west had persuaded Stalin to deport rather than exile him, and in 1936 he was back in France, able to witness from a safe distance the Great Purge in which most of his comrades were evaporated, in which his wife Liuba Russakova was hounded into a psychiatric hospital, and his mother-in-law with her sons and their wives disappeared into the Gulag; the writings he had left behind suffered the fate that would have been his own had he remained.What makes Serge stand out for me is his uncompromising refusal to be forced into anybody's ideological box. His principles and ideals were clear, and he insisted that there could be no lowering of the benchmark: all human beings must have the right to enough food, a home, the means to earn a living, and to live their lives in peace, alongside all their other fellow human beings, with a system of justice that itself models justice while ensuring it. Nothing less. So he attacked Stalin for the Great Purge and the millions who had died of cold and starvation in the name of overthrowing Feudalism, and the European Communists refused to publish him (though many were happy to pay for his typesetting skills for those writers they were prepared to publish), even attacked him for his perceived disloyalty to the Socialist cause. Only in Belgium, and there only in a labour organisation newspaper that few read, was he able to state and re-state his convictions, railing against those in Moscow who would appease Hitler.

When Paris fell to the invaders, Serge left in a hurry; his books were burned, and his seat on the train to the death-camps was awaiting him. The United States refused to grant him political asylum, so he went to Mexico, where he spent the last years of his short life, writing, and single-parenting his artist son Vlady, until he died of a heart attack on November 17th 1947.

In his splendid foreword to the English translation of "Memoirs of a Revolutionary", Adam Hochschild speaks of Serge's "ability to see the world with unflinching clarity... In the Soviet Union's first decade and a half, despite arrests, ostracism, theft of his manuscripts, and not having enough to eat, he bore witness. This was rare. Although other totalitarian regimes, left and right, have had naïve, besotted admirers before and since, never has there been a tyranny praised by so many otherwise sane intellectuals." But not Serge, who yearned for its success, but refused to accept the delusion when it was so obviously failing.

That clarity, that refusal to be fooled by PR and propaganda, is everywhere in his writings. Here, for example, speaking about Zeitgeist and Quondam opinions, the absence of independent thought:

“The inconsequentiality of human testimony is astonishing. Only one in ten can record more or less clearly what they have seen with any accuracy; can observe it, and remember it - and then be able to recount it, resisting the suggestions of the press and the temptations of their own imaginations. People see what they want to see, what the press or the questioners suggest.” (page 45)

Or here, in a paragraph that infers the same case for permanent revolution that Trotsky made, likewise seeing the failure of the revolutionaries to establish a new order after overthrowing the previous one, the reason why all revolutions end up in the hands of tyrants - this at the time of the Spanish Civil War:-

“The only example we had till then was that of the Paris Commune, which, looked at closely, was not very encouraging: indecision, rifts, empty chatter, personality clashes between nonentities... The Commune, just like the Spanish Revolution later, threw up heroes by the thousand, admirable martyrs by the hundreds, but it had no head. I thought about this often as it seemed to me that we were heading towards a Barcelona Commune. The masses, overflowing with energy, moved by a muddled idealism, lots of middle-level leaders - and no head.” (page 65)

A description of the Arab Spring of 2012 might not read any differently, in Libya and Tunisia, in Egypt...

I first encountered Serge during the fifty days of my own experience of jail; my elder daughter sent me three books, a complete Shakespeare (every Desert Island abandonee gets one, usually with a King James Bible!), "The Story Of Art" by E.H. Gombrich (five hundred pages of text to enchant my mind, four hundred of pictures to gratify my senses - beautiful choice). And the Serge, of whom I had never heard, despite my decades long interest in Russian literature and politics. But I knew she had chosen wisely when I went straight to the glossary in search of favourite and familiar names, and there were almost all of them, Gumilev and Akhmatova and Yesenin and Pasternak in the poetry corner (no Mandelstam or Babel, but perhaps not surprising), Gorky and Trotsky and all the expected in the political corner; and then, just surfing randomly to get a flavour, I knew that he was going to become important to me when the first piece my eyes alighted on read:

“I endured the long, enriching experience of cell life, allowed no visits or newspapers, with only the squalid statutory rations (which were picked at by all the thieves on the staff), and some good books. I understood, and ever since have always missed, the old Christian custom of retreats which men spent in monasteries, meditating face-to-face with themselves and with God, in other words with the vast living solitude of the universe. It will be good if that custom is revived, in the time when man can at last devote thought to himself. My solitary confinement was difficult, often more than difficult, suffocating, and I was surrounded by awful suffering and I did not escape - did not seek to escape - any of the troubles that could have come my way (except for T.B., of which I was afraid), seeking to exhaust them, demanding the greatest efforts of myself. Furthermore, I believe that, however bitter the situation, one ought to go all the way for the sake of the others and for oneself so as to gain from the experience and to grow from it. I also believe that a very few simple rules will suffice for that end: physical and intellectual discipline, exercise (absolutely necessary for the man in a cell), walks for meditation (I did my six miles around the cell every day) intellectual work, and recourse to that light exaltation, or light spiritual exaltation, which is provided by great works of poetry. Altogether I spent around fifteen months in solitary confinement, in various conditions, some of them quite hellish.” (page 44)

There were so many noteworthy phrases that I found myself, over the next several days, repeatedly having to grab a coloured pencil to highlight yet one more (no book is worth reading if it doesn't require a black pencil for notes and a coloured highlighter pen to mark the best fragments): "A light heart is a heavy burden", on page 25, was merely a pleasing turn of phrase; "Man is Nature become conscious of itself" on page 39 could have been borrowed from a hundred other writers; but they set a tone, and it was obvious there would be substance soon enough.

And so there was, whole paragraphs, sometimes whole pages of it - pages 54-55 for example, too long to copy here, which excoriate the French prison service of his day in much the same terms that the Supreme Court of California had recently condemned the one in which I was sojourning. Others in which he described his early realisation (I can confirm that he is right) that survival in such a place is a matter of feigned obedience, pragmatic friendships, and sheer bloody will, and that of these three the latter matters most, forcing oneself to eat the muck that is provided for food, exercising the body and the mind, keeping thoughts of women under control, refusing to be lured into either hope or despair (this is the hardest part, the false hope especially)... but the personal is already made easier when you are reading Serge in his French prison, or in his Petrograd cell in 1919, and he is telling you that his experience is nothing when compared to Shalamov's in Kolyma; and I am grinning, because I know those Kolyma tales extremely well, because the last tale is the only known eye-witness account of Mandelstam's last days in Voronezh, and the penultimate adds a third Kuznetsov to my account in "Going To The Wall".

But all of that is just the local, the superficial. When he comments on politics he becomes eternal and universal.

"Clarity" is Hochschild's term, and perhaps he was thinking specifically of this paragraph:

For any of you who are now minded to read his book, or even just parts of it, his splendid portrait of Lenin can be found on pages 119 and 120, with his own favourite quote from Lenin on page 133, a summary indeed of everything that was wrong with Bolshevism from the outset and went wrong with Communism until it ended: "It is a terrible misfortune that the honour of beginning the first Socialist revolution should have befallen the most backward people in Europe."

As to Trotsky, who he respected enormously even when, occasionally, he disagreed with him, his account of "the Old Man" leading the Red Army into battle can be found on pages 108-111, his evaluation of him at the height of his power and influence on pages 164-166, his account of his ideological disagreements with him on pages 406-408. A detailed account of the purge which destroyed not only Trotsky but Kamenev, Zinoviev, other leaders from the period before Lenin's death, Serge himself amongst them, can be found from page 244 until 279 (but see also pages 294/5, 301/2, 320 and 325 especially) though the really full account is the one in the novel "The Case of Comrade Tulayev".

What Serge seems to have understood, beyond the narrow confines of his own failed revolution, is the inevitable failure of ideology anywhere, including the ideology of religion (which is not the same thing as theology). What he says about Bolshevism is equally true of the Vatican, or its equivalents in Islam, Capitalism, Democracy, or any of the other absolutist belief systems that we convince ourselves are the manifestations of good and right:

Dostoievski said exactly the same thing in "The Grand Inquisitor", and Hannah Arendt in her account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann.

But all of that is just the local, the superficial. When he comments on politics he becomes eternal and universal.

"World capitalism, after its first suicidal war, was now clearly incapable either of organising a positive peace, or (what was equally evident), of deploying its fantastic technological progress to increase the prosperity, liberty, safety, and dignity of mankind." (page 133)

"Clarity" is Hochschild's term, and perhaps he was thinking specifically of this paragraph:

“I give myself credit for having seen clearly in a number of important situations. In itself, this is not so difficult to achieve, and yet it is rather unusual. To my mind, it is less a question of an exalted or shrewd intelligence, than of good sense, goodwill, and a certain sort of courage to enable one to rise above both the pressures of one's environment and the natural inclination to close one's eyes to facts, a temptation that arises from our immediate interests and from the fear which problems inspire in us. A French essayist has said: 'What is terrible when you seek the truth, is that you find it.' You find it, and then you are no longer free to follow the biases of your personal circle, or to accept fashionable clichés. I immediately discerned within the Russian Revolution the seeds of such serious evils as intolerance and the drive towards the persecution of dissent. These evils originated in an absolute sense of possession of the truth, grafted upon doctrinal rigidity. What followed was contempt for the man who was different, of his arguments and way of life. Undoubtedly, one of the greatest problems which each of us has to solve in the realm of practice is that of accepting the necessity to maintain, in the midst of intransigence which comes from steadfast beliefs, a critical spirit towards these same beliefs and a respect for the belief that differs. In the struggle, it is the problem of combining the greatest practical efficiency with respect for the man in the enemy - in a word, of war without hate.” (page 374)

For any of you who are now minded to read his book, or even just parts of it, his splendid portrait of Lenin can be found on pages 119 and 120, with his own favourite quote from Lenin on page 133, a summary indeed of everything that was wrong with Bolshevism from the outset and went wrong with Communism until it ended: "It is a terrible misfortune that the honour of beginning the first Socialist revolution should have befallen the most backward people in Europe."

As to Trotsky, who he respected enormously even when, occasionally, he disagreed with him, his account of "the Old Man" leading the Red Army into battle can be found on pages 108-111, his evaluation of him at the height of his power and influence on pages 164-166, his account of his ideological disagreements with him on pages 406-408. A detailed account of the purge which destroyed not only Trotsky but Kamenev, Zinoviev, other leaders from the period before Lenin's death, Serge himself amongst them, can be found from page 244 until 279 (but see also pages 294/5, 301/2, 320 and 325 especially) though the really full account is the one in the novel "The Case of Comrade Tulayev".

What Serge seems to have understood, beyond the narrow confines of his own failed revolution, is the inevitable failure of ideology anywhere, including the ideology of religion (which is not the same thing as theology). What he says about Bolshevism is equally true of the Vatican, or its equivalents in Islam, Capitalism, Democracy, or any of the other absolutist belief systems that we convince ourselves are the manifestations of good and right:

"Bolshevik thinking is grounded in the possession of the truth. The Party is the repository of truth, and any form of thinking that is different from it is dangerous or reactionary error. Here lies the spiritual source of its intolerance." (page 156)

Dostoievski said exactly the same thing in "The Grand Inquisitor", and Hannah Arendt in her account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann.

"I am quite convinced that a sort of natural selection of authoritarian temperaments is the result. Finally, the victory of the revolution deals with the inferiority complex of the perpetually vanquished and bullied masses by arousing in them a spirit of social revenge, which in turn tends to generate new despotic institutions." (page 156)

“For all these reasons, even the great popular leaders themselves flounder within inextricable contradictions which dialectics allows them to surmount verbally, sometimes even demagogically. Twenty or maybe a hundred times, Lenin sings the praises of democracy and stresses that the dictatorship of the proletariat is a dictatorship against 'the expropriated possessing classes,' and at the same time, 'the broadest possible workers’ democracy.' He believes and wants it to be so. He goes to give an account of himself before the factories; he asks for merciless criticism from the workers. Concerned with the lack of personnel, he also writes, in 1918, that the dictatorship of the proletariat is not at all incompatible with personal power, thereby justifying, in advance, some variety of Bonapartism. He has Bogdanov, his old friend and comrade, jailed because this outstanding intellectual confronts him with embarrassing objections. He outlaws the Mensheviks because these 'petty-bourgeois' Socialists are guilty of errors that happen to be awkward. He welcomes the anarchist partisan Makhno with real affection, and tries to prove to him that Marxism is right, but he either permits or engineers the outlawing of anarchism. He promises peace to religious believers and orders that the churches are to be respected, but he keeps saying that 'religion is the opium of the people'. We are proceeding towards a classless society of free men, but the Party has posters stuck up nearly everywhere announcing that 'the rule of the workers will never cease'. Over whom then will they rule? And what is the meaning of this word rule? Totalitarianism is within us." (page 157)

You can find David Prashker at:

Copyright © 2017/2024 David Prashker

All rights reserved

The Argaman Press

No comments:

Post a Comment